What is health insurance?

It seems like this is a silly question, but it’s really not. Health insurance is something everyone should have, many people need, and not everyone has access to. It’s a contract typically between an employer and an insurance company under which employees can have various medical procedures paid in part by the insurance company in exchange for paying a set amount for the policy.

Clear as mud, right? Let’s try to make that easier. We are going to concentrate on employer policies in this series since that is where the workers of Local 26 get their insurance, although there are certainly individually purchased policies as well.

Insurance companies offer a wide variety of options to employers to choose when putting together a benefit package for their employees. Depending on what choices the employer makes, those options are bundled into policies employees can choose during open enrollment or after a significant life event (birth, death, adoption, marriage, etc.). The insurance company does not tell the employer which options they may choose; all options are on the table. It just depends on how much an employer is willing to offer (and of course how much they are willing to pay) for those options.

Once an employer chooses which benefit package(s) they are going to offer their employees, the employee is given a list of those packages from which to choose. Some include nothing but medical (both doctors and facilities), some also add prescription, vision, dental, and/or hearing coverage. Usually adding more options to a policy costs more for the employee. The employer determines how much each employee will pay for their insurance premium and how much the employer is willing to pay on the employee’s behalf. Under union-negotiated collective bargaining agreements, usually those amounts are a large part of negotiations in addition to wages and working conditions.

Premiums can be either entirely employer contributed (as is the case with most of Local 26’s agreements) or partially paid by employees either through payroll deduction or direct payment. Sometimes it’s a combination of both such as when employer contributions do not equal the price of a premium, as often happens with stagehands.

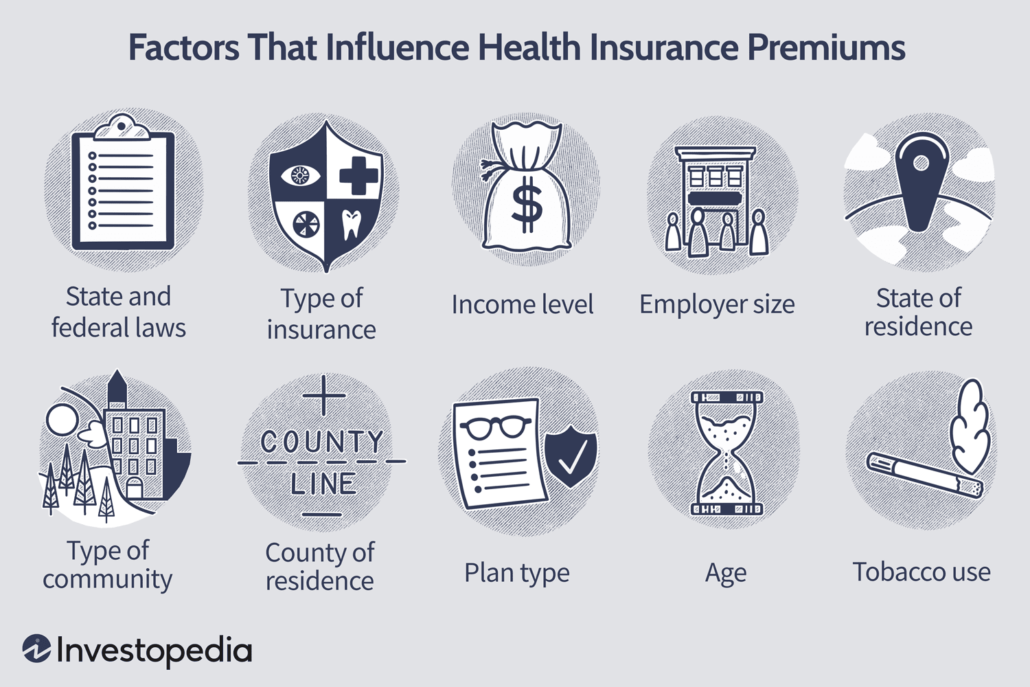

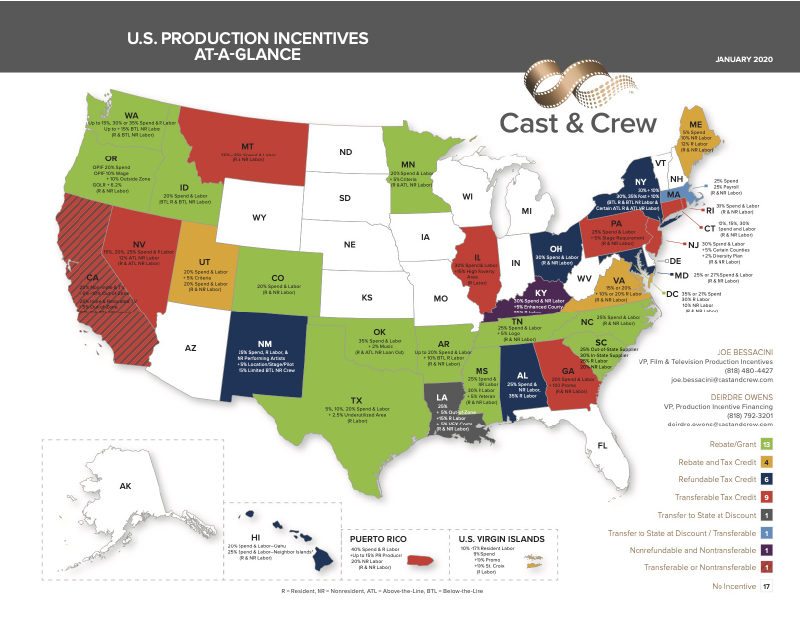

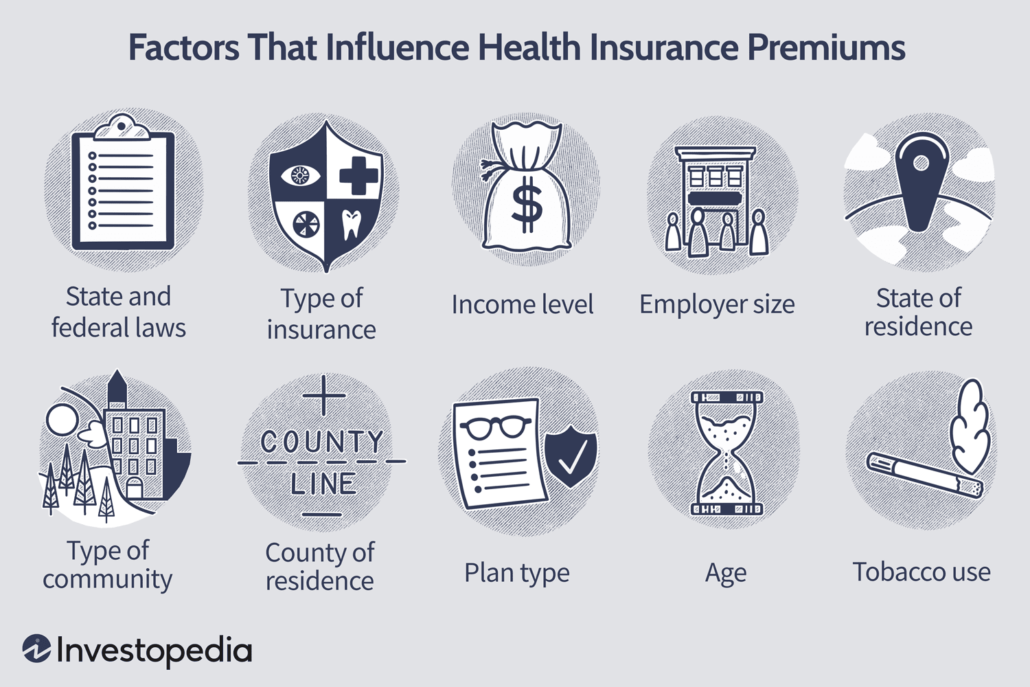

Many factors go into determining how much your health insurance premium will be. Not all factors affect all premiums, especially in union-negotiated contracts. But certainly state and federal laws, what type of insurance, employer size, state and county of residence, and plan type are factors. As all prices change depending on those factors, so too does the cost of insurance.

Another factor is often what deductible a policy carries. High deductible policies tend to carry much lower premiums. This is because the employee takes the risk that they will not end up needing to use their health insurance for much so they pay less for the policy in exchange for having to pay more medical expenses out of pocket. On the flip side, policies with a high premium typically have a lower deductible. These policies are good for those who know they will have considerable medical expense and won’t be able to afford much up front.

It’s important to note the employer also determines what packages they offer will charge for a deductible. They also choose how much of a percentage in coinsurance an employee pays, and how much their out of pocket maximum will be per year.

I’m throwing too many phrases out there that many folks don’t understand. Let me put this simply:

Premium = how much it costs for your insurance policy.

Deductible = how much you pay for medical expenses up front before your health insurance starts paying anything.

Coinsurance = the percentage split between your responsibility and what the insurance company pays.

Out of Pocket Maximum = The highest amount you will pay for medical expenses in a calendar year, after which your insurance company pays everything.

Those are very simplified and of course there are factors that affect them as well, but they are the basic definitions.

For example: Sally Smith has an insurance policy, and their premium is $1300 per quarter. That is how much Sally must pay (or their employer must contribute) in order for them to have insurance coverage every three months.

Sally’s deductible is $1000, meaning the first $1000 of any medical services Sally receives must be paid by them entirely with no help from their insurance.

Once that deductible is met, Sally’s policy becomes 80/20. This means Sally’s insurance company pays 80% of medical expenses and Sally is responsible for 20%.

Sally’s out of pocket maximum is $3000. This means Sally continues to pay 20% of all medical expenses until they have paid a total of $3000 for all medical services received that year. Once that out of pocket maximum is met, Sally’s insurance company pays 100% of medical services until January 1st of the next year. On January 1st, all those numbers are reset to zero and Sally must once again meet the deductible before insurance starts paying, and so on.

Another term you need to know is Copay. A copay is a set amount of money for specific services. For example, a doctor’s office visit carries a $30 copay. Copays are entirely your responsibility until you reach your out of pocket maximum for the year and are not figured into deductible or coinsurance. So in our Sally example above, Sally will pay a $30 copay for each doctor’s visit they have until they meet their out of pocket maximum.

While copays do not contribute to deductible or coinsurance, they DO contribute to out of pocket maximum in most cases. So it’s entirely possible Sally will not have to pay 20% of ALL medical services if they have numerous copays that contribute to their out of pocket maximum.

Altogether, the deductible, coinsurance, copays, and out of pocket maximum are called Cost Share. Simple way to think of it: Cost Share is the amount an employee is responsible for paying for their medical services.

Another important thing to know is the difference between In Network providers and Out of Network providers. In Network providers (doctors, facilities, etc.) have agreed to accept an insurance company’s negotiated discount as full payment for their services. Out of Network providers are under no obligation to accept the lesser amount as full payment.

For example: Sally goes to an in network doctor. That doctor charges $350 for the services performed, but Sally’s insurance company has negotiated with the doctor for a maximum payment of $175. The most that doctor can legally be paid for those services is $175, and they cannot bill anyone for the remaining $175.

If, however, Sally went to an out of network doctor, the rules change. The doctor will still charge $350 for the services, and Sally’s insurance will still allow a maximum payment of $175. That stays the same. But the doctor can then bill Sally for the remaining $175 and they will be responsible for paying it.

This is the difference between Charged Amount and Allowed Amount.

Charged Amount = what a provider charges for a medical service.

Allowed Amount = what an insurance company is willing to pay for that service.

In network providers must accept the allowed amount as full payment. Out of network (also known as non-participating) providers can balance bill (also known as surprise bill) the patient for the remainder.

It is always best to go to in network providers whenever possible. You will be guaranteed the best available rates that way with no surprise bills later. A person’s cost share is figured on the insurance company’s allowed amounts for services. There are typically higher dollar amounts for deductible and a higher percentage of coinsurance out of network as well.

Using our Sally example, their in-network deductible is $1000, but their out of network deductible could be $2500. Their in-network coinsurance is 80/20, but their out of network coinsurance could be 60/40. And their out of pocket maximum could be anything including not having a maximum at all out of network.

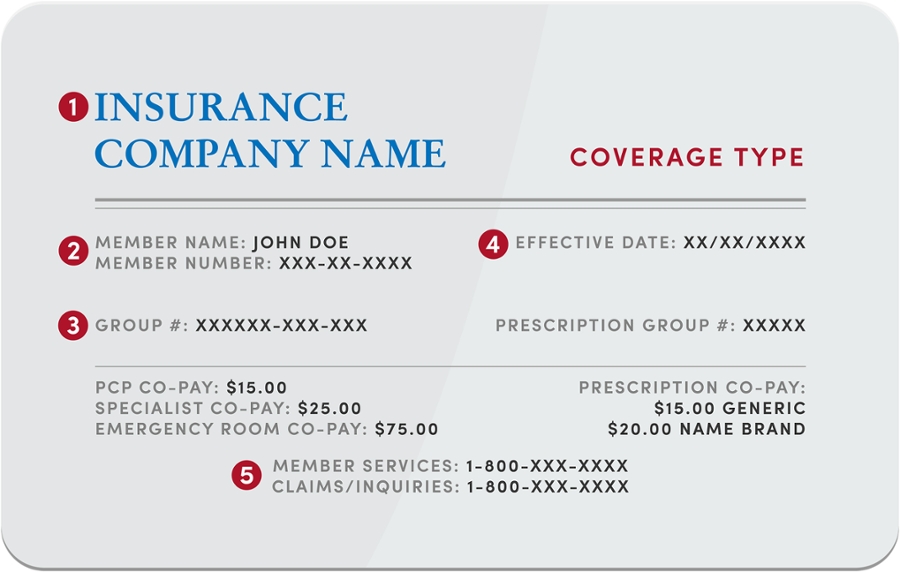

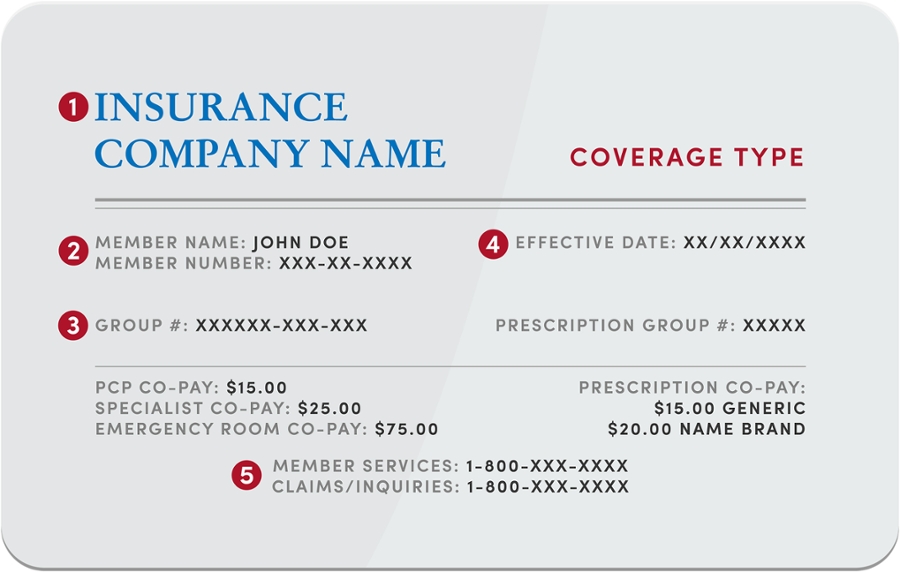

The last thing I want to touch on today is the information you should have available when contacting your health insurance company about benefits or claims.

ALWAYS have your insurance card with you when you call! Under very stringent federal and other privacy laws (I’m sure you’ve heard of HIPAA), they must verify who they are speaking with to determine how much, if any, information can be given. They are absolutely not allowed to discuss more than general information with anyone unless you give your express permission, even your spouse. Some aspects of your medical treatment (sexually transmitted diseases, pregnancy-related services, mental health and substance abuse treatment to name the most common) they are not allowed to discuss with anyone but you period. You can give your permission to discuss those things, but it will have to be done on each phone call.

They will need your subscriber ID (sometimes called an enrollee ID), full name, birth date, address and/or ZIP code, and a phone number where you can be reached. If you are calling about someone else on your policy, they will need their full name and birthdate as well. They need this before they can even see your policy to answer questions. Conveniently, the number you need to call to ask questions is located on your card, so you’ll probably have it out anyway.

Depending on what you’re asking, they will need further information, but I’ll get into that in future posts in this series. The goal is not to overwhelm anyone with information, but to make it easier to understand health insurance!